Expansion vs. Innovation?

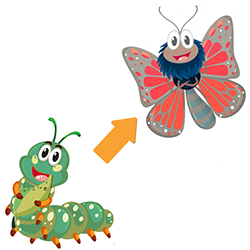

![]() Innovation & transformation involves much more than expansion & improvement

Innovation & transformation involves much more than expansion & improvement

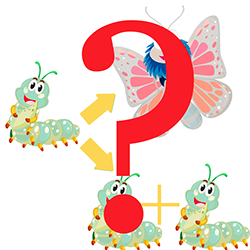

What research guides growth?

Not all research translates into implementation & impact when helping programs to grow.

Not all research translates into implementation & impact when helping programs to grow.

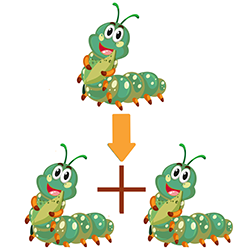

Where are the leaders?

Know what you need in a leader, and match them care-fully to your program's goals.

Know what you need in a leader, and match them care-fully to your program's goals.

Are you ready to grow?

Can you incorporate the new approaches, stark feedback, and partnerships needed?

Can you incorporate the new approaches, stark feedback, and partnerships needed?

Countdown to startup

![]() A timeline for the leadership, resources, and preparation needed to launch

A timeline for the leadership, resources, and preparation needed to launch

Coming Soon

Where are the Leaders?

Finding leaders who can innovate, incubate, and transform programs

July 28, 2017

As described elsewhere, true innovation and program transformation involves much more than a simple expansion or improvement of an existing program, or replication of a program developed elsewhere. To innovate, you need a clear vision of a new program model, you need to carefully plan its implementation, you need to anticipate barriers, and/or you need to build new relationships across disciplines, agencies, and sectors. Any of these place markedly increased demands on a program leader, as outlined below.

As described elsewhere, true innovation and program transformation involves much more than a simple expansion or improvement of an existing program, or replication of a program developed elsewhere. To innovate, you need a clear vision of a new program model, you need to carefully plan its implementation, you need to anticipate barriers, and/or you need to build new relationships across disciplines, agencies, and sectors. Any of these place markedly increased demands on a program leader, as outlined below.

In this section, I provide detailed descriptions of the qualities you might seek in a candidate expected to lead true program innovation, incubation, or transformation. These are listed in the approximate order in which they are likely to be found. This list also includes

Warning Signs in leadership that could suspend or abort the launch of more ambitious program development, and

Warning Signs in leadership that could suspend or abort the launch of more ambitious program development, and

All Clear Signs in leadership that could help to re-start the launch of more ambitious program development.

All Clear Signs in leadership that could help to re-start the launch of more ambitious program development.

Though few leaders will demonstrate all of the qualifications below, understanding these qualifications will help ask the right questions of candidates, and help determine how ambitious you might be given the available candidates. More importantly, you may be able to align more ambitious program goals with the specific qualities that a leader might bring. This has important implications for the program development process: the best alignment is achieved when candidates for leadership position have an opportunity to propose different options for program development based on the candidate's particular experience.

Though consultants and leadership teams can help implement program expansion, improvement and replication, they cannot have the same impact on more ambitious program development efforts

Though consultants and leadership teams can help implement program expansion, improvement and replication, they cannot have the same impact on more ambitious program development efforts

In describing how to evaluate candidates to lead program expansion, improvement, or replication, several options were offered when the right candidate could not be found. These options including using consultants or creating a team to provide supplemental expertise, experience, and support. This is not an effective solution, however, when the right leader cannot be found for more ambitious program development. Why? Most efforts at innovation require balancing multiple, new, and often poorly defined sets of factors at once, and the modeling how these might change and interact over time. This is not something easily done by a team.

Consider an effort to create a new multidisciplinary treatment team for a new clientele. This might require that we establish how these different interventions can be funded and coordinated, while also being assured that there is a likely stream of clients available to sustain our new team once established. In theory, you might assemble different people with the expertise needed in each of these areas to outline the possibilities. But in practice, this is very difficult. Emerging ideas are more difficult to communicate effectively within a team, let alone with stakeholders and others implicated in the decision to move forward with the initiative. You may need to simultaneously test several new ideas (like the best way to fund a team, to coordinate the work of different disciplines, and so on), and smoothly coordinating input about progress from different team members would be tricky. Perhaps you can enlist different champions who each address a different component (funding, training, medical intervention, behavioral intervention), but each champion whose specific area of expertise must be assuaged when that component is changed or eliminated. And if you are successful in assembling the key players, you must make sure to allot the additional time required from each, and lengthen the launch.

The qualities described below can help to identify a leader capable of undertaking significant program reform

The qualities described below can help to identify a leader capable of undertaking significant program reform

Organizations also regularly replace existing leaders who have retired, have left for their own reasons, or who have been let go. Sometimes these new leaders are then expected to initiate reforms. Perhaps the need for reform is sparked by the very problems that compelled the termination of the last leader. Perhaps a leader who has retired or left to pursue other opportunities did not initiate improvements - or even to let quality slip - during the final months or even years of their tenure. Or perhaps the organization simply views the transition as an opportunity to clean house. In most cases, the leader will need some additional qualities to be successful: having expertise in an area designated for improvement, or some program management experience, will simply not suffice. Those leaders undertaking reform will need relevant experience in training, program development, working with advocates, or other specific qualities listed below, depending on the specific nature of the reform sought.

Reform places special demands on leaders. They must be able to accurately evaluate the program they are tasked with leading. They must be able to engage front-line staff, organization leadership, and other stakeholders. They must balance the frank discussion of weakness with the need to generate enthusiasm for the needed changes. And they must do it all without losing the momentum and good will gained when they were first hired. Those considering candidates for such leadership positions should carefully evaluate the communication and team-building skills of applicants, and especially any experience leading other organizations through period of change..

For each of the qualifications listed below, an actual record is far more compelling than a description of experience or ideas

For each of the qualifications listed below, an actual record is far more compelling than a description of experience or ideas

Most of the criteria listed below consider a candidate's reported experience, with multidisciplinary teams, program development, advocates, and so on. Whenever possible, seek evidence of the actual record. The more substantial the reported effort, and the greater the impact sought, the more likely it is that there is some written document that corroborates the account, at least to some degree. This could take the form of a project or funding proposal, a written agreement, an internal memorandum outlining a plan for action, or a literature review outlining the research supporting an initiative.

The opinion of a candidate can turn in an instant when the only record of grand project they described is a poorly written proposal that lacks any details regarding implementation. I am especially wary when terms like "innovation" and "research-based" are used. These imply that information about other efforts has been gathered and evaluated, in which case the candidate should be able to share original sources if not the candidate's summary itself . Otherwise, unsupported claims of research-based innovation - indeed, any claim that candidate might make without some evidence - become suspect.

1. Record of research or scholarship

At some point, a candidate for more ambitious program development will have to be able to produce documents that describe their program in detail. Why? First, these more ambitious efforts cannot typically be undertaken with additional time and resources, at least during the planning and launch phase. This will require a detailed proposal for external funders, or for those decision makers within the organization who must re-allocate existing resources. Second, most proponents of more ambitious proposals will want others to learn about their efforts: leaders in the public sector will expect their programs to be replicated, leaders in the private sector will want others to seek out their guidance, and leaders in academia will need to present and publish their findings. Candidates should be able to produce examples of grants, and paper or conference presentations, that demonstrate that they can create a compelling case for program development.

These same examples should also illustrate the candidate's capacity for scholarship. Do they understand other models of services and training? Can they critically compare and contrast these models with their own? The bar is even higher for those programs that aspire to build on the best available science: can the candidate assess the lessons offered by existing research?

Experience conducting outcome research is rarely sufficient to prepare a candidate to lead true innovation or transformation

Experience conducting outcome research is rarely sufficient to prepare a candidate to lead true innovation or transformation

Though a record of research and scholarship is certainly desirable in a candidate seeking to lead more ambitious program development, the typical university-based researcher aspiring to this impact will almost always need some other skills and experience. Some researchers eagerly claim the potential to build innovative programs of service or training, based solely on research findings that to date have only had implications for outcomes: in these cases, the potential for innovation can only be assessed once the effectiveness of a specific program has actually been tested. Even then, there are many critical unknowns. Most outcome research is initially conducted under very controlled conditions in highly specialized settings: can the same outcomes be achieved with a broader population, and with community-based professionals and programs? Most outcome researchers have relatively little experience delivering services or training outside of university-based settings, and can easily under-estimate the challenges involved. And researchers who have spent a career studying a specific problem in a specific population of people with ASD are susceptible to overstating the impact on a broader population.

2. Experience leading multidisciplinary teams

The greater the ambition of a new program of services and training, the more likely it will depend upon careful coordination across multiple disciplines. In such cases, it is essential that the program leader fully understand the scope of practice and expertise of each discipline. This can help them draw on n important lesson: Multidisciplinary teams magnify the reach and impact of individual disciplines by drawing on the strengths and role of each.

In training scores of professionals across school, hospital, and university settings over the past 20 years, I have found deep-rooted misunderstandings that can lead one group to cursorily dismiss the contributions of another. Too many teams are multidisciplinary in name only: different professionals each conduct their own assessments and generate their own recommendations and reports, and rarely change their practices or recommendations in response to feedback from other professional groups.

Even under the best of circumstances, simply working as a member of a multidisciplinary team does not really prepare you to lead one, let alone craft a new multidisciplinary model. A leader not only needs to fully understand a professional's take on their scope of practice, they need to be able to look behind it to identify gaps, and then embark on the very delicate task of re-negotiating a role for that professional based on this assessment. Failing at this task can fuel deep seated inter-professional rivalries. Succeeding helps not only to make best use of the professionals available, but sets the stage for colleagues to learn from one another.

3. Experience building collaborative partnerships across agencies

Services and training programs for people with ASD often function in silos (Doehring, 2013). Schools do not always collaborate well with hospitals, hospitals with universities, and so on. There are many different reasons why agencies struggle to build fruitful collaborations with other agencies, and especially agencies in other sectors. The best collaborations occur when agencies have complementary programs and/or resources, and but this presumes that each agency can recognize and value some aspect of services or training that they might not fully understand. Other important lessons when trying to integrate research, because turning research into community practice requires collaboration across researchers, practitioners, and agencies.

The problem is that schools, hospitals, community services, and universities have different missions, operate under different funding structures, may serve different populations, and often employ different kinds of professionals. Similar silos can exist within a sector, between more and less specialized settings. A community based pediatric practice and specialized children's hospital will refer patients to each other, but otherwise may not collaborate to modify their practices based on the feedback of the other. Misunderstanding and missed opportunity abound.

And there are other reasons. Some agencies are simply too competitive or too inflexible to be collaborative. Sometimes collaboration breaks down because leaders are simply not adept at the give-and-take of building a relationship between organizations. And there may be pragmatic barriers to funding or coordinating these complementary activities, that one or both of the agencies lacks the resources or the ideas to overcome. For families who must negotiate this maze of services, this lack of collaboration between agencies create unnecessary delays to getting their child the help they need.

The best candidates have already learned an important lesson: Collaborative networks multiply the impact of new initiatives when they carefully draw on the strengths of each partner. Program leaders identifying opportunities for improvement should always look first for potential partners. Mutually benefiting from a partner agency's expertise and resources is one of the most cost-effective ways to improve outcomes in a program and to begin to address overall system capacity. But the success of these efforts requires a leader who not only fully understands their own program, but one who can recognize when another program's role could be important, and then undertake the delicate negotiations required. Sometime the process by which leaders emerge is itself a barrier: the highly driven, competitive, self-assured people who naturally advance into leadership positions in some organizational cultures are ill-suited to build these kinds of collaborative partnerships.

The ideal candidate has negotiated a contract or other form of inter-agency agreement that defined the responsibilities of each agency towards a common goal. Other evidence is less definitive. Candidates may have overseen a partnership that they did not negotiate. Candidates who have worked in different sectors may be able to reflect on their own misunderstanding once they move from one sector to another.

4. Experience designing and delivering more comprehensive programs of professional development

Ask someone about their training experience, and most people might list a series of lectures they have given or courses they have taught or workshops they have led. This kind of experience is often insufficient, especially for more ambitious projects. Why? Lectures and workshops may convey the capacity to share information, but not to change practice. A well-designed post-graduate course can test competence using real-world cases, but is typically only available as part of a degree program, often targeting only one professional group. This is very different from the training required to spur program growth.

Most ambitious expansions of services and training rely on an even more comprehensive and coordinated approach to professional development, as described in my 2013 book. This draws on another important lesson: Create tiered professional development programs that tailor content to the role and expertise of each staff and agency. Professional development must be tailored to the role of each professional, often includes case-based coaching and feedback, reaches all stakeholders and partner agencies, and must be adapted to the changing needs of each type of staff member as the program evolves and expands. Each choice is resource intensive for the trainer (to develop one hour of training, I can easily allot 3-10 hours of preparation depending on the topic), and for the trainees and the organization (a two hour training for 20 staff is equivalent to one week's salary for one of the trainees!!). The best candidates have already learned an important lesson: Build professional development around core principles that translate research into practice guidelines with clear outcomes. A related lesson helps to integrate plans for training and staffing: Create a pipeline of core professionals, and assemble the resources needed to build and sustain their expertise.

The roles and responsibilities of program leader and of a consultant are very different in more comprehensive and coordinated professional development. Most trainer-consultants deliver a product and walk away. Only when you have become a program leader held accountable for your program's progress do you begin to recognize the need for a more comprehensive and coordinated approach to training, the challenge of creating it, and the costs of delivering it.

Be wary of applicants who claim to have developed comprehensive training programs but who cannot provide associated materials

Be wary of applicants who claim to have developed comprehensive training programs but who cannot provide associated materials

Everyone can claim to have been an excellent trainer, but how many can provide you with written materials? Maybe they cannot because someone else actually developed and owns the training... Maybe they cannot because their training involves talking at trainees without a script. Maybe maybe the only thing they can provide are powerpoint slides crowded with information. In any case, training that does not include materials other than powerpoints (like bibliographies, fidelity checklists, exercises, readings/bibliographies, and so on) and activities other than lectures (like case studies, discussion groups, pilot data collection, and so on), arranged in a meaningful timeline with specific goals, is unlikely to be either comprehensive or effective.

An applicant who demonstrates how they cultivated new experts through training can develop capacity much more rapidly

An applicant who demonstrates how they cultivated new experts through training can develop capacity much more rapidly

Anyone who has tried to build capacity knows that the greatest barrier, after the lack of leaders, is the lack of experts. As described above, some expertise is seeded through specialized graduate and post-graduate training. Our capacity to create these kinds of experts is limited, and what they gain through more extensive training in a specialized site might be offset by the relative lack of real-world experience.

Some candidates may have already learned an important lesson: To expand competence or to increase capacity, you must cultivate new experts recruited within the organization. These home-grown experts are practicing professionals who have an innate drive to become even better in a particular area. They are eager to explore new ideas, even those than challenge their current approach. Experienced leaders know how to identify potential experts, and engage them through specialized training and expanded responsibilities. Over time, these experts can begin to help with training and other program development activities, and free up a program leader for other important tasks. And eventually, some of these experts become the next generation of leaders.

Successful program incubation depends on this process. As described elsewhere, incubation must result in new, community-based programs that have the capacity to improve and expand. This requires the creation of a new generation of experts and leaders within these community-based agencies. The training in this case is much broader, and must address other skills that support continued program development, as described in the next section.

5. Personal experience with disability

An increasing number of professionals have themselves grown up with a sibling or child with ASD or a related condition. While close collaboration with advocates can help shift priorities, there is no replacement for living with disability. As described elsewhere, the drive to close gaps through services and training gains greater urgency and focus when a leader has lived with these gaps. The ability to draw on personal experience can help a leader quickly establish credibility with consumers and advocates.

6. Effective relationships with advocates

The rise of advocates has overturned the traditional approach to program development, at least in the USA. Self-advocates and caregivers of those with ASD have started to reshape priorities that program leaders and policy makers have grown used to setting. Advocates now bring discussions about research findings and implications into the public sphere, and demand action. Advocacy groups such as Autism Speaks have mobilized new funding sources, though much of this new funding thus far has focused on supporting traditional research and not on developing innovative programs of services and training.

The rise of advocates has posed special challenges for traditional program leaders, who often struggle to develop effective partnerships with them. Advocates are more likely to fundamentally question traditional programs of services and training, and by extension the leaders of those programs. At the very least, today's leaders must be prepared to frankly and honestly address these concerns without becoming defensive. The best leaders have already learned an important lesson: Advocates must help to decide which services should be prioritized for their own child and for the overall program. These leaders recognize the unique and invaluable perspective of those living with ASD, and develop an agenda that engages advocates as equal partners. Indeed, gaps in services and training that are identified by advocates offer the greatest potential for an immediate impact for more ambitious programs. And people living with ASD are much more compelling advocates for change, especially for publicly funded programs.

Ask any candidate for a leadership position, and they will claim to understand the importance and perspective of advocates. But what is the candidate's actual record? Every candidate should be able to cite examples of fundamental shifts in their approaches or priorities that can be traced directly back to the influence of an advocate. Many leaders might describe how they sought the input of advocates, but what evidence can they offer that this input was decisive, and that advocates were treated as equal partners?

7. Experience in developing programs

Comprehensive and coordinated training is certainly one important element of program development, but other elements are equally important and often overlooked. In each of the examples listed below, the best candidates have already learned an important lesson: Improving and expanding services in a coordinated and sustainable way requires planning, expertise, and leadership. These candidates offer more than ideas: they can describe very specific examples of what they have accomplished. And these further underscore the difference between the program management experience described elsewhere as important to expansion, and the capacity for leadership required for true transformation. The latter requires leaders who can design new programs from scratch, and not simply implement a program designed by someone else.

- Program design: If you trying to demonstrate a new treatment or training model, for example, what are the critical components? How must these be delivered, and how do you establish that these have been delivered effectively? How do you plan to roll out this new model? An experienced candidate can offer detailed examples of how they might address these questions.

- Evidence-based practice: What is currently recognized as best practice, and what is the research supporting this practice as opposed to other related practices (Reichow, Doehring, Cicchetti, and Volkmar 2011)? A candidate capable of building on the latest research should be able to describe what kind of research is relevant (offering specific examples of outcome research studies) , and what kind of breakthroughs might change the recommended practices.

- Funding and staffing: The best ideas for new services and training are useless without the infrastructure to deliver them - namely, staffing and funding. A candidate should be able to offer an example of a detailed staffing plan that clearly lists the range of responsibilities, and the effort and experience needed to fulfill them. A candidate should also be able to list the funding sources they can draw upon, and how this might shift during the development and implementation phases. This draws on important lessons about the inter-relationship between staffing, funding, and outcomes: Design staffing models and professional development to ensure the desired treatment fidelity and treatment intensity, and ;Optimize the amount and type of staffing support needed by creating a schedule that maps activities by intensity and expertise.

- Policy: More ambitious program development will require changing the existing policies or developing new ones to support the decisions outlined above. What are examples of policies the candidate has changed or developed?

- Planning: The more ambitious program development may need to draw on another important lesson: Launching a complex program in phases helps to maintain focus on specific goals, and to document progress for funders. Does the candidate have experience with a multi-step process of planning and implementation?

Taken together, this experience in program development might offer a lesson that protects against the temptation of prematurely investing in physical facilities: Don't begin by investing in a new building unless you are sure that your program will be effective and sustainable.

A candidate experienced in program development, comprehensive training, and forging partnerships can incubate new programs

A candidate experienced in program development, comprehensive training, and forging partnerships can incubate new programs

Given the excitement in the business community regarding the role of incubators and accelerators in supporting technology start-ups, it is not surprising that others would be eager to translate this concept into the development of new program of services and training related to ASD,and ignite the same excitement. As described elsewhere, incubation is a term best reserved for a specific set of activities that results in the creation of a new and effective program capable of replicating itself. Some of the qualifications outlined above can be used to identify the leader capable of incubating programs, with the support of the right kind of parent program.

- These leaders must be able to undertake the kind of significant program development activities described in this section.

- Developing new areas of competence and expertise in the professionals providing services and training depends on comprehensive and coordinated training, another important skill to evaluate among candidates.

- Negotiating the kind of support that a parent program provide to a program to be incubated, and how that support evolves over time, requires candidates experienced in establishing partnerships between agencies.

Related Content

On this site

Do you need a new leader?

Do you need a new leader?

Who can lead an expansion?

Who can lead an expansion?

Warning Signs that could suspend or abort a launch

Warning Signs that could suspend or abort a launch

All Clear Signs that could re-start a launch

All Clear Signs that could re-start a launch

Expansion vs. Innovation?

![]() Innovation & transformation involves much more than expansion & improvement

Innovation & transformation involves much more than expansion & improvement

What research guides growth?

Not all research translates into implementation & impact when helping programs to grow.

Not all research translates into implementation & impact when helping programs to grow.

Where are the leaders?

Know what you need in a leader, and match them care-fully to your program's goals.

Know what you need in a leader, and match them care-fully to your program's goals.

Are you ready to grow?

Can you incorporate the new approaches, stark feedback, and partnerships needed?

Can you incorporate the new approaches, stark feedback, and partnerships needed?

Countdown to startup

![]() A timeline for the leadership, resources, and preparation needed to launch

A timeline for the leadership, resources, and preparation needed to launch

Coming Soon

X

My Presentations and Publications

(2011). With Brian Reichow, Dominic Cicchetti, & Fred Volkmar F. (Eds.). Evidence-Based Practices and Treatments for Children with Autism. Springer-Verlaug, New York, NY.

(2011). With Brian Reichow, Dominic Cicchetti, & Fred Volkmar F. (Eds.). Evidence-Based Practices and Treatments for Children with Autism. Springer-Verlaug, New York, NY.

Guideposts

![]() Straight Lines Build professional development around core principles that translate research into practice guidelines with clear outcomes

Straight Lines Build professional development around core principles that translate research into practice guidelines with clear outcomes

![]() Simple Steps Multidisciplinary teams magnify the reach & impact of individual disciplines by drawing on the strengths and role of each.

Simple Steps Multidisciplinary teams magnify the reach & impact of individual disciplines by drawing on the strengths and role of each.

![]() Simple Steps Advocates must help to decide which services should be prioritized for their own child and for the overall program.

Simple Steps Advocates must help to decide which services should be prioritized for their own child and for the overall program.

![]() Simple Steps Launching a complex program in phases helps to maintain focus on specific goals, and to document progress for funders.

Simple Steps Launching a complex program in phases helps to maintain focus on specific goals, and to document progress for funders.

![]() Simple Steps Create a pipeline of core professionals, and assemble the resources needed to build and sustain their expertise

Simple Steps Create a pipeline of core professionals, and assemble the resources needed to build and sustain their expertise

![]() Simple Steps Don't begin by investing in a new building unless you are sure that your program will be effective and sustainable

Simple Steps Don't begin by investing in a new building unless you are sure that your program will be effective and sustainable

![]() Other Lessons Collaborative networks multiply the impact of new initiatives when they carefully draw on the strengths of each partner

Other Lessons Collaborative networks multiply the impact of new initiatives when they carefully draw on the strengths of each partner

![]() Other Lessons To expand competence or to increase capacity, you must cultivate new experts recruited within the organization

Other Lessons To expand competence or to increase capacity, you must cultivate new experts recruited within the organization

![]() Other Lessons Improving and expanding services in a coordinated and sustainable way requires planning, expertise, and leadership

Other Lessons Improving and expanding services in a coordinated and sustainable way requires planning, expertise, and leadership

![]() Other Lessons Turning research into com-munity practice requires collaboration across researchers, practitioners, and agencies

Other Lessons Turning research into com-munity practice requires collaboration across researchers, practitioners, and agencies

![]() Other Lessons Create tiered professional development programs that tailor content to the role and expertise of each staff and agency

Other Lessons Create tiered professional development programs that tailor content to the role and expertise of each staff and agency

![]() Other Lessons Optimize the amount and type of staffing support needed by creating a schedule that maps activities by intensity and expertise

Other Lessons Optimize the amount and type of staffing support needed by creating a schedule that maps activities by intensity and expertise

![]() Other Lessons Design staffing models and professional development to ensure the desired treatment fidelity and treatment intensity

Other Lessons Design staffing models and professional development to ensure the desired treatment fidelity and treatment intensity