Expansion vs. Innovation?

![]() Innovation & transformation involves much more than expansion & improvement

Innovation & transformation involves much more than expansion & improvement

What research guides growth?

Not all research translates into implementation & impact when helping programs to grow.

Not all research translates into implementation & impact when helping programs to grow.

Where are the leaders?

Know what you need in a leader, and match them care-fully to your program's goals.

Know what you need in a leader, and match them care-fully to your program's goals.

Are you ready to grow?

Can you incorporate the new approaches, stark feedback, and partnerships needed?

Can you incorporate the new approaches, stark feedback, and partnerships needed?

Countdown to startup

![]() A timeline for the leadership, resources, and preparation needed to launch

A timeline for the leadership, resources, and preparation needed to launch

Coming Soon

What research can guide efforts to improve and transform ASD services and training?

July 28, 2017

The descriptions in this section focus on the growth of ASD programs delivering services and training instead of conducting research. There is a good reason: ASD programs focused on research set different priorities, draw on different resources, seek different outcomes, require different expertise, and operate on a different timeline. But that does not mean that research is irrelevant to our task. Indeed, some research can be critical to guiding the growth of specific programs of ASD services and training, though perhaps not the kind of research most might think. And as long as these misunderstandings persist, the gap between what outcome research tells us is possible and the outcomes actually achieved by people living with ASD will continue to widen.

The descriptions in this section focus on the growth of ASD programs delivering services and training instead of conducting research. There is a good reason: ASD programs focused on research set different priorities, draw on different resources, seek different outcomes, require different expertise, and operate on a different timeline. But that does not mean that research is irrelevant to our task. Indeed, some research can be critical to guiding the growth of specific programs of ASD services and training, though perhaps not the kind of research most might think. And as long as these misunderstandings persist, the gap between what outcome research tells us is possible and the outcomes actually achieved by people living with ASD will continue to widen.

So how do we draw a straight line from research to implementation to impact when helping programs of services and training to grow and improve? In this section, I distinguish between

Research that can immediately shape the growth of ASD services and training

Research that can immediately shape the growth of ASD services and training

Research that may only sometimes shape ASD services and training, and

Research that may only sometimes shape ASD services and training, and

Research that thus far has had little to no meaningful impact on ASD services and training

Research that thus far has had little to no meaningful impact on ASD services and training

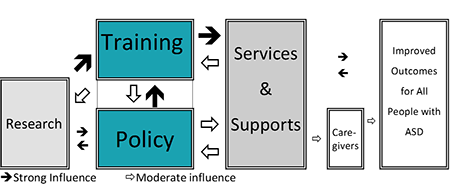

A core principle here, and discussed in detail in my 2013 book, is that the immediate impact of research on outcomes for people with ASD is always mediated by the services received directly by people with ASD, or by the person who supports them.  As illustrated in this diagram, research does not ever impact services directly, but through its influence on training and policy. The more relevant that research is to services needed by people with ASD, the greater the impact on outcomes. And it is important to remember that not all outcomes are equal. Some outcomes are unequivocally important to the person's quality of life (like the ability of adults to live and work independently).

As illustrated in this diagram, research does not ever impact services directly, but through its influence on training and policy. The more relevant that research is to services needed by people with ASD, the greater the impact on outcomes. And it is important to remember that not all outcomes are equal. Some outcomes are unequivocally important to the person's quality of life (like the ability of adults to live and work independently).

Research on the outcome of specific treatments for people with ASD

Research on the outcome of specific treatments for people with ASD

Research that tests the outcomes of specific interventions is directly relevant to the design of ASD services and training (Reichow, Doehring, Cicchetti, and Volkmar 2011). In this kind of research, a treatment is delivered to people with and/or without ASD under conditions that allow us to attribute any observed improvements to the treatment itself. Ideally, the treatment is delivered to the same kind of people who will participate in the programs we want to improve, and in a manner mimicking real-world conditions. Systematic reviews that generate specific recommendations based only on high quality outcome research studies are the most powerful. These recommendations can determine which treatments should be prioritized when programs are expanded or improved. This helps to draw on a powerful lesson: build professional development around core principles that translate research into practice guidelines with clear outcomes.

Consider systematic reviews that have established that a specific technique like differential reinforcement (or DR) is effective in decreasing aggression, but find no evidence that another technique like sensory integration (or SI) is similarly effective. I have used these kinds of reviews to design whole programs of services around DR and related evidence-based practices: how I select candidates for DR, what kinds of professionals I need to design and deliver a program using DR; how intensively DR must be delivered; how quickly I should expect results using DR, and; how to fund the resources needed. Other reviews suggests that there may even be enough research to break recommendations for DR down by target and/or function (Doehring, Reichow, Palka, Philips, & Hagopian, 2014). I have designed wide range of training programs that teach us how and why to use DR and other evidence-based practices for aggression instead of SI, for staff in hospital (Doehring, 2013)and school programs (Doehring, 2006) I have led, and across the full range of interns.

So those interested in program improvement and transformation should pay special attention to outcome research, and especially those systematic reviews that establish a given intervention as evidence-based. The recommendations arising from such research, and especially systematic reviews, provide immediate opportunities for program growth. A partnership between a community-based provider looking to expand or improve services and a scientist conducting outcome research can help to immediately translate research into more widespread practice, with the right planning and collaboration across agencies. And those settings that deliver services AND conduct research might prioritize research that tests specific interventions.

Research on gaps in desired services and outcomes for people with ASD

Research on gaps in desired services and outcomes for people with ASD

Research that evaluates gaps in the services that people with ASD receive and the outcomes they achieve can also help in designing programs of services, and, to a lesser extent, how we design programs of training (Doehring, 2013) . In this kind of research, a population of people with ASD is surveyed with respect to the services they received, the needs they have, and the outcomes they achieved. In most cases, these services, needs, and outcomes are assessed indirectly, by having the respondents or their caregivers complete a survey. In any case, this kind of research can reveal gaps across populations (for example, delays in accessing timely diagnosis) and disparities affecting particular groups (for example, that those from racial or ethnic minorities experience relatively greater delays). This kind of research can help to anticipate these gaps and disparities, and design services to eliminate some of the likely barriers, or design training to help practitioner anticipate these gaps in their own work.

Consider the the well-documented gap in transition services for students with ASD from low-income populations. This gap was a key factor in the design of the Transition Pathways Proposal, which prioritized strategies for improving access to these groups for transition services. These gaps can also influence training, by helping sensitize trainees to the challenges underserved groups face when accessing services. One example as the inclusion of ASD Screening in homeless shelters as an activity for LEND Trainees.

So those interested in program improvement and transformation should also pay special attention to research on gaps in outcomes and services. These can offer easier opportunities to adapt existing programs or develop new ones to specifically target known gaps across regions, skills, and populations. A partnership between a community-based provider looking to expand or improve services and a researcher who has identified gaps can help to develop new services and policy to immediately mitigate the impact of these gaps. And those programs that deliver services AND conduct research might draw on an important lesson, by conducting surveys to identify critical gaps in access to basic care, and to set benchmarks for new program priorities.

Research on the characteristics of people with ASD

Research on the characteristics of people with ASD

Research that evaluates the characteristics of people with ASD can have an impact on the growth of programs, as long as that characteristic can help to inform decisions about services being provided to people with ASD. This distinction is critical, as some characteristics can be important to a theory about ASD, but without an obvious connection to treatments or services associated with important life outcomes for people with ASD (Doehring, 2013).

For example, the co-occurring mental health conditions that can complicate ASD are characteristics that directly impact important life outcomes and, by extension, can guide the growth of ASD services and training. Consider the anxiety that occurs in a surprising proportion of people with ASD at some point in their lives. Anxiety can not only be debilitating, but can also respond to a variety of interventions. Research that identified the prevalence of anxiety and its impact on people with ASD also helped to inform decisions about how programs of services might improve and expand to better address anxiety. Updates to ASD training programs have begun to include this emerging knowledge about the role and impact of anxiety. A similar lesson can be drawn regarding intellectual disabilities, namely that service providers should consider broadening eligibility requirements, since many practices and programs for ASD are effective for those only with ID.

The relevance of characteristics deemed important only to theories of ASD is less clear. Consider the very extensive body of research amassed over the past 20 years that describes the difficulties that people with ASD have in understanding the perspective of another person. Though these difficulties in perspective taking are one of the core features of ASD, we have yet to discover a specific and unique relationship with important life outcomes, or interventions that specifically and effectively target this area of difficulty. Perhaps such relationships or interventions will emerge in the future, but until then, it is hard to imagine how research on theoretically important characteristics could meaningfully shape the growth of specific programs of services, or the training to support such growth.

So those interested in program improvement and transformation should be cautious about trying to use research on ASD's characteristics to guide their program's growth, unless those characteristics are clearly linked with important life outcomes. Those programs that deliver services AND conduct research intended to immediately improve outcomes might think twice about prioritizing research that evaluates characteristics of ASD that so far have only demonstrated theoretical importance.

Research on the possible causes of ASD

Research on the possible causes of ASD

Research that seeks to establish the possible causes of ASD has rarely had any meaningful impact on decisions about how programs of services and training might improve and transform. Why? Simply because such research has not identified any single, specific cause clearly linked to a significant proportion of cases of ASD, or any cause amenable to intervention (Doehring, 2013).

There have been some important exceptions. Fifty years ago, for example, Bernard Rimland and Michael Rutter used neurological and genetic findings to argue that ASD was a neuropathological disorder. This was critical to overturning the prevailing psychoanalytic claims that ASD was caused by poor parenting, and setting the stage for the emergence of treatments based on education and applied behavior analysis. And efforts to de-bunk theories that ASD's rise is due to the MMR vaccine have been key to maintaining the high rates of vaccination needed to ensure public health (at east in most areas of the country).

And of course, research on ASD's causes might yet suggest new paths to intervention. But until then, it is not clear how research will be relevant to those seeking guidance in improving outcomes now. And so those programs that deliver services AND strive to conduct research ostensibly intended to improve outcomes now might think twice about about investing in research that explores the causes of ASD.

Related Content

Autism Spectrum News (2017 Fall Issue)

What kind of research can guide the growth of ASD services?

Read more about the different categories of research relevant to ASD practice and policy.

On this site

Expansion vs. Innovation?

![]() Innovation & transformation involves much more than expansion & improvement

Innovation & transformation involves much more than expansion & improvement

What research guides growth?

Not all research translates into implementation & impact when helping programs to grow.

Not all research translates into implementation & impact when helping programs to grow.

Where are the leaders?

Know what you need in a leader, and match them care-fully to your program's goals.

Know what you need in a leader, and match them care-fully to your program's goals.

Are you ready to grow?

Can you incorporate the new approaches, stark feedback, and partnerships needed?

Can you incorporate the new approaches, stark feedback, and partnerships needed?

Countdown to startup

![]() A timeline for the leadership, resources, and preparation needed to launch

A timeline for the leadership, resources, and preparation needed to launch

Coming Soon

X

My Presentations and Publications

Doehring, Peter, Reichow, B., Palka, T., Philips, C., & Hagopian, L. (2014). Behavioral Approaches to Managing Intense Aggression, Self-Injury, and Destruction in Children with Autism Spectrum and Related Developmental Disorders: A Descriptive Analysis. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23 (1) 25-40.

Doehring, Peter, Reichow, B., Palka, T., Philips, C., & Hagopian, L. (2014). Behavioral Approaches to Managing Intense Aggression, Self-Injury, and Destruction in Children with Autism Spectrum and Related Developmental Disorders: A Descriptive Analysis. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23 (1) 25-40.

(2013).. Doehring, Peter. From Compliance to Excellence: Creating Standards of Practice to Drive Program Development. Autism New Jersey, Atlantic City, NJ (October).

(2013).. Doehring, Peter. From Compliance to Excellence: Creating Standards of Practice to Drive Program Development. Autism New Jersey, Atlantic City, NJ (October).

(2011). With Brian Reichow, Dominic Cicchetti, & Fred Volkmar F. (Eds.). Evidence-Based Practices and Treatments for Children with Autism. Springer-Verlaug, New York, NY.

(2011). With Brian Reichow, Dominic Cicchetti, & Fred Volkmar F. (Eds.). Evidence-Based Practices and Treatments for Children with Autism. Springer-Verlaug, New York, NY.

(2006). Independent peer review of behavior plans for students with autism in a specialized public school program. Association for Behavior Analysis. Atlanta GA.

(2006). Independent peer review of behavior plans for students with autism in a specialized public school program. Association for Behavior Analysis. Atlanta GA.

Guideposts

![]() Straight Lines Barriers to accessing services are well-established: include under-served groups from the start when testing a new service

Straight Lines Barriers to accessing services are well-established: include under-served groups from the start when testing a new service

![]() Straight Lines Build professional development around core principles that translate research into practice guidelines with clear outcomes

Straight Lines Build professional development around core principles that translate research into practice guidelines with clear outcomes

![]() Straight Lines Use large, well-designed surveys to identify critical gaps in access to basic care, and to set benchmarks for new programs

Straight Lines Use large, well-designed surveys to identify critical gaps in access to basic care, and to set benchmarks for new programs

![]() Simple Steps Consider broadening eligibility requirements, since many practices and programs for ASD are effective for those only with ID

Simple Steps Consider broadening eligibility requirements, since many practices and programs for ASD are effective for those only with ID

![]() Other Lessons Turning research into com-munity practice requires collaboration across researchers, practitioners, and agencies

Other Lessons Turning research into com-munity practice requires collaboration across researchers, practitioners, and agencies