Some background on prevalence research

September 23, 2016

Highlights

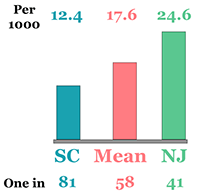

The Centers for Disease Control or CDC published their most recent estimates of ASD's prevalence in April 2016. These estimates place ASD’s prevalence amongst 8 year olds at 1 in 68 children, or about 1.5% of the overall population. These estimates have been steadily increasing since the CDC first began issuing them almost 10 years ago. The findings published by the CDC appeared to confirm earlier reports from other researchers suggesting a possible increase in the rate of ASD, and to address some of the questions about whether ASD was being properly diagnosed. These apparent increases over time had already led to rampant speculation about possible causes of ASD.

This estimate of the true number of children with ASD is also significant when it is compared to two other numbers. First, this estimate appears to be much greater than the number of children actually identified with ASD by health and education professionals - what we would call administrative prevalence. Second, this appears to be greater still than the number of children who are actually receiving specialized ASD services.

These possible discrepancies are not academic. A missed diagnosis of ASD can have very real, very immediate, and very important consequences. Children with ASD who are missed by health or education professionals are much less likely to receive any treatments or services developed for ASD. All of the research we do to develop the best treatments becomes meaningless if we cannot deliver these treatments to the children who need them. When we miss a child, we miss a chance to change their life (and the lives of their parents and other family members) for the better. And we have to remember that being identified with ASD does not guarantee that you will actually get the right kind of specialized treatment.

As a statewide director for a specialized public school program serving children with ASD, I was extremely worried about these apparent discrepancies and the possible increases in the prevalence of ASD over time. How many children with ASD were we missing? Are there specific kinds of children we are especially likely to miss? Who is missing them? How are we missing them? Are they getting any help at all for behaviors related to ASD?

As an agency leader, I wanted to know what would it take to properly identify all children with ASD, so that we could provide them with the education they need. This led me to initiate a statewide effort to implement the best possible assessments of ASD, to ensure that we were not over-diagnosing ASD. Expanding a comprehensive and specialized public school program consumed time and resources, and I had to assure other leaders and policymakers that we had verified the need for expansion. In the process, I experienced the lag between research, practice, and outcomes: once a gap had been identified, at least 3 years were required before program changes could be developed and implemented statewide. In the interim, more children missed opportunities to benefit what research had already told us were effective practices for identification and intervention.

This experience led me to carefully consider the different routes and barriers to early and accurate identification. A good place to begin is the specific methodology used and the results obtained by the CDC. Can we begin to estimate how many we might be missing, how we might have missed them, who we might be especially likely to miss, and how this might help us to identify strategies for closing gaps in identification and intervention? This series of opinion pieces are meant to address these questions.