Invest in program development

November 30, 2016

A lesson I have learned is that program development takes a lot of time and planning, especially funding and assembling the increased staffing support needed during the development, launch, and expansion phases, and so I framed the primary mission of the gift-funded backbone as program development. A detailed staffing plan to support all of these goals is outlined on a separate page on this site. This staffing plan drew extensively on important lessons learned in developing other successful programs.

What Is Program Development?

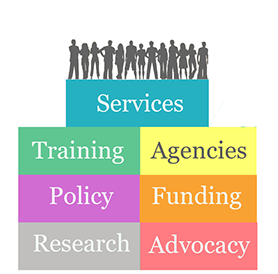

I have found that service organizations will always trim program development costs under fiscal pressure before trimming general administrative overhead and direct services. As a result, they are poorly positioned to maintain program development, let alone invest heavily in significant expansion or improvement. I drew on my 2013 review of state and national programs to define dimensions of program development - to provide increased staff training, to create new school and employment opportunities, to coordinate effort across agencies, to create and begin to implement new policies, and to provide planning for and oversight of program change. This definition distinguishes program development direct care and general management, and provides the foundation for defining specific job responsibilities and projecting staffing needs.

Before You Begin

Assure a critical threshold of direct services

Based on my experience launching comparable programs in other settings, I have learned that an investment in program development is only worthwhile if the current level of direct services is intense enough to support the addition of new program elements. Teachers and assistants who struggle because of inadequate staffing levels, very little training or support, or a mix of students on wildly different needs (especially those with intense behavioral challenges) will have great difficulty becoming engaged in helping to develop a new program. This can be seen in an earlier lesson in which I mapped out the types of staffing resources likely needed to provide direct services across the day.

In the initial stages of developing the Transition Pathways Proposal, I defined a minimum intensity relative to individual and small group teaching (2-3 hours/day), and sought to assure that classes would be relatively homogeneous with respect to educational level and level of co-occurring intellectual disability, without the need for significant individualized support to address intense behavioral challenges. After a very careful review, I concluded that existing staff levels at the school level could be adequate if supplemented by new job coaching resources made available by WIOA, combined with the creative use of natural supports (peer mentors, co-workers, and so on) supported by coaching, at least for Year One of the two-year of the program. As discussed in a later chapter, establishing this minimum threshold of direct staffing support is also critical to establishing overall funding levels, because direct staffing support is often the most significant cost for day to day program operation.

Develop a staffing plan to support Program Development

Researchers, clinicians, advocates, and other program leaders who have never undertaken significant program development invariably underestimate the staffing resources needed. They often assume that a single part- or full-time equivalent position is needed to provide training, This trend was apparent in my 2014 review of leadership positions created through state legislation. For the Transition Pathways Proposal, I developed a staffing plan including 3.5 FTEs based at Drexel to primarily support program development activities during the launch phase, by allocating different tasks to different team members according to their role and level of expertise. For example, day-to-day management tasks were divided between a full-time Director and part-time Assistant Director, while many hands-on coaching and training activities were assigned to Specialists (described later). This staffing plan clearly distinguished between program development and direct services, operationally defined different components of program development, and allocated some aspects of program development and direct service to be shared between the Pathways team and staff from partner agencies.

Strategies for Implementing Program Development

Plan on intense training and coaching during the launch

When introducing a new service or intervention, it is important to build in additional support during the launch period. This support can involve decreasing the student:staff ratios (by decreasing group size or adding support from an assistant or a coach) and/or allocating additional time to review progress and discuss possible tweaks. Both of these goals can be accomplished by assigning an additional staff member to an activity during a start-up period. For services that we intended to introduce (e.g., expanding the traditional IEP and transition-planning to incorporate person-centered planning), I had planned on utilizing Transition Pathways Staff to initially co-lead planning meetings.

Actively foster the growth of expertise

One important gap I have encountered in developing and implementing a plan for program expansion and improvement is the lack of expertise in specific topic areas. We sought to address this by carefully building on existing areas of competence within partner agencies and faculty at the AJ Drexel Autism Institute, and adding 1-2 specific areas of increased expertise through use of consultant contracts. I expected to draw on consultants for hands on guidance of front-line staff, and to help incubate in-house expertise, and so engaging consultants who have themselves provided direct services in community-based agencies was key. We expected to invest in some specific areas in an initial phase. I sought to emphasize foster better cross-agency transition planning, given previous lessons about the importance of case coordination. My colleagues sought to develop a self-advocacy curriculum and related set of activities. I viewed this as liked to a broader plan to utilize the Drexel backbone to incubate experts. This drew on my earlier successes in structuring professional development to cultivate the emergence of experts from within our own ranks.

Anticipate the leadership gap

In designing the Transition Pathways Proposal, I applied an earlier and important lesson: that those advocating for new programs underestimate the availability and importance of experienced program leaders, especially during a development and launch phase. In addition to offering to lead Transition Pathways, I also outlined a scenario in which leadership responsibilities are shared, to take advantage of the likely experience of available leaders. Although leadership is best provided by a single person, a leadership team that together possesses the requisite skills and experience, supported by external consultants addressing specific gaps in expertise, can create the structure necessary to make the decisions required. I described how a leadership team might be relatively more effective during the management of an established project. During the development phase, however, a leadership team may have less flexibility to identify emerging ideas, or negotiate changing roles with partners, because the knowledge and capacity for action needed is spread out across multiple individuals.

Assure that advocates play a pivotal role

Another important gap in many new programs is the failure to engage advocates (both transition-aged individuals on the autism spectrum, and their caregivers) in the design and delivery of the program. I had learned an important lesson earlier in my career, that advocates offered a unique and an essential perspective on the priorities set for a program. For a program like Transition Pathways, self-advocates (graduates of the program or other college students on the spectrum) can offer tremendous insights into program priorities and methods. Some programs seek input from advocates by soliciting their feedback once or twice during the design process: I sought to create an active advisory committee that would remain engaged throughout. I also created a part-time advocate-coach position, to specifically hire a college student on the spectrum to advise the program and to provide coaching to staff, co-workers, teaching faculty, and peers.

Related Content

On this site

My Presentations and Publications

(2016). ![]() Innovative approaches to developing a multi-agency, college-based ASD transition program. November. Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence Conference, Columbus, OH.

Innovative approaches to developing a multi-agency, college-based ASD transition program. November. Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence Conference, Columbus, OH.

Guideposts

![]() Simple Steps For programs that depend on the involvement of multiple agencies, anticipate the resources needed to ensure coordinated care

Simple Steps For programs that depend on the involvement of multiple agencies, anticipate the resources needed to ensure coordinated care

![]() Simple Steps Advocates must help to decide which services should be prioritized for their own child and for the overall program.

Simple Steps Advocates must help to decide which services should be prioritized for their own child and for the overall program.

![]() Other Lessons There is no natural pipeline of leaders trained and experienced in undertaking comprehensive program development

Other Lessons There is no natural pipeline of leaders trained and experienced in undertaking comprehensive program development

X

![]() Other Lessons To expand competence or to increase capacity, you must cultivate new experts recruited within the organization

Other Lessons To expand competence or to increase capacity, you must cultivate new experts recruited within the organization