Are methods for establishing prevalence accurate enough?

September 23, 2016

Highlights

It is helpful to understand how the accuracy of the CDC's file review method is calculated. A sample of children in the CDC's study is tested using the CDC's file review method, and a comprehensive diagnostic assessment. Each child's results are put into one of the 4 cells of the table to the right.

If the results of the comprehensive assessment and the file review were in perfect agreement, then all of the children in the study would fall either into the 1st or the 4th cells of the table, and we feel more confident that the prevalence estimate generated using the file review method is probably accurate. Researchers accept, however, that there will be some disagreements between the two methods.

- The file review method might result in an incorrect diagnosis of ASD. In this case, we would suspect that the file review method might over-estimate the true prevalence of ASD, as indicated by blue text in the table to the right.

- The file review method might miss a possible diagnosis of ASD. In this case, we would suspect that the file review might under-estimate the true prevalence of ASD., as indicated by the red text in the table to the right.

Has the accuracy of the file review method been tested?

The fact that the ADDM study protocol does not include in-person, comprehensive assessments to confirm a diagnosis has led some to question whether the cases identified by the ADDM reviewers really have ASD. A well-controlled 2011 validation study compared results obtained using the ADDM file review method with results obtained via rigorous and comprehensive diagnostic assessments conducted by independent experts.

Three groups of children were selected from one of the ADDM sites. Together, these groups represented the entire sample of eligible children, and so their results should generalize to the broader population. These children's files had already been reviewed as part of the prevalence study.

- 225 children had no red flags in their file when reviewed in the original ADDM study. Of these, 103 agreed to participate in the validation study.

- 96 children had red flags in their file when reviewed in the original ADDM study, but were not subsequently labeled with ASD by ADDM reviewers. Of these, 40 agreed to participate in the validation study.

- 53 children had red flags in their file when reviewed in the original ADDM study, and were subsequently labeled with ASD by ADDM reviewers. Of these, 34 agreed to participate in the validation study

A total of 177 children therefore participated in the validation study. All of these children received comprehensive diagnostic assessments.

All together, the protocol correctly classified 158 out of 177 children. The two methods agreed that ASD was present in 27 cases, and absent in 131 cases. The errors in identifying ASD were instructive

- The ADDM file review method was quite specific; that is, 32 of the 39 cases identified with ASD using the ADDM file review protocol proved to have ASD when independently evaluated using a gold standard protocol. Seven children were falsely diagnosed with ASD using the file review protocol, as indicated in blue in the figure to the right.

- The authors found that the ADDM file review method was not as sensitive as expected; that is, it missed 12 children who were determined to have ASD when independently evaluated using a gold standard protocol. 12 children were missed using the file review protocol, as indicated in red in the figure to the right.

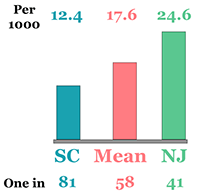

Taken together, these results mean that the CDC's file review method is more likely to underestimate than overestimate ASD's “true” prevalence. Using the file review method alone, we would have concluded that ASD was present in 34 cases; conducting a complete assessment would have yielded 39 cases. Therefore, estimates based solely on a file review method may under-estimate ASD's prevalence by about 15%.

What this tells us about how we might miss ASD

These methods suggest that there are at least three ways we can "miss" or fail to catch ASD, and one way that ASD might be over-identified using the CDC's methods. This is summarized in the diagram and described in the text below. In the next chapter, I distinguish between Later in this series, we describe how certain kinds of children are more likely to be missed in one of these three ways, and what the consequences might be. The way a child is missed tells us how we might close each gap.

Related Content

ADDM: 2016 CDC Report

Does this child have ASD?

Based on Clinical assessment

YES NO

YES Agree Disagree

Child has Review falsely

ASD diagnosed ASD

NO Disagree Agree

Review Child does

missed ASD not have ASD

177 File Reviews

Results of 2011 CDC study

Did the child have ASD, based on

177 Clinical assessments

YES NO

YES Agree Disagree

27 7

NO Disagree Agree

12 131

177 File Reviews

What did the 2011 validation study tell us about children missed or misdiagnosed by the original ADDM file review method?

Conclusions drawn from clinical assessment

Original conclusions drawn from ADDM file review

177 files were originally reviewed by ADDM; the same 177 children were clinically evaluated for ASD in the 2011 study

2. ASD was missed in 4 (4%)

1. Children with ASD but without a file were never assessed

103 files had no red flags and so these files were never fully reviewed

99 (96%) were correctly labeled

74 files had red flags, and so these were thoroughly reviewed

ASD was diagnosed in 34 files

ASD was not diagnosed in 40 files

4. 7 (20%) were incorrectly labeled

27 (80%) were correctly labeled

3. ASD was missed in 8 (20%) cases

32 (80%) were correctly labeled

39/177 cases assessed or treated at specialized centers were diagnosed with ASD following a full clinical assessment.

So, a File Review...

Catches most (69%) ASD cases

Misses some (31%) cases

Underestimates prevalence (by 17%)

Misses ?? cases never referred to a center

1. An unknown number of children with ASD had no file and so were never screened. These children were completely missed

I have not seen any studies from the ADDM network that estimate how many children might have ASD but do not have records at specialized health or education centers. In the next chapter in this series, I propose one method for estimating the number of children who might be completely missed in this way. In South Carolina, for example, we may be completely missing 1 child for every child identified with ASD by ADDM reviewers. Later in this series, I will speculate about who these children might be, and the consequences of being completely missed in this way. But in general, these children are getting no help for ASD or related developmental concerns.

2. Red flags were completely missed by professionals in 10% of children later diagnosed with ASD

In the 2011 validation study, 4 children identified with ASD by the ADDM reviewers had no red flags in their health or education file. While this represented only about 4% (e.g., 4 out of 103) files that had been screen negative, it nonetheless represented 10% (e.g., 4 out of 39) children subsequently diagnosed with ASD in this sample. In these cases, professionals had completely missed the signs of ASD: for every 9 cases of ASD diagnosed, 1 case might be missed in this way. Later in this series, we will speculate about who these children might be, the kind of help they might be receiving, the kind of help they may still be missing, and the specific kind of training professionals will need to close this gap.

3. In 20% of children later diagnosed with ASD, some signs of ASD are detected, but the diagnosis was missed

In the 2011 validation study, 8 of the 39 children identified with ASD by the ADDM reviewers had some red flags in their health or education file. In these cases, professionals had caught behaviors of concern, but did not diagnose ASD. For every 3 to 4 cases of ASD accurately identified using the file review method, 1 case might be missed in this way.

These professionals are making some valid observations, but may simply need more training to interpret these correctly. In the meantime, these children are getting specialized assessment or treatment for other kinds of conditions, perhaps addressing some of the difficulties related to their ASD that were detected by the professionals involved. These professionals may need different training that those in Group 2. For example, they may need much more extensive training in the signs of ASD. In the meantime, these children are at least getting specialized assessment or treatment for other kinds of conditions, but this help is less likely to address all of the difficulties related to their ASD. We will elaborate on each of these possibilities later in this series.

4. For every 4 files correctly labeled with ASD, 1 file was mislabeled,

The validation study also revealed that the file review method can incorrectly label someone with ASD. Twenty seven cases of ASD were correctly identified using the file review method, but 7 more cases proved not to have ASD when a complete assessment was conducted.

Conclusion: These prevalence estimates are strong enough to use as general guideposts to identify gaps

Taken together, these findings do not suggest that the CDC's file review method grossly under- or overestimates ASD 's prevalence. The file review method is not as accurate as a full clinical assessment when considered on a case-by-case basis, but the overall number of children identified with ASD using the file review method was only slightly less than the number identified using a full clinical assessment.

As discussed earlier in this series, there is considerable debate among epidemiologists about whether these methods are accurate enough to fulfill the primary goal they have established for prevalence research: that is, to generate a "true" estimate of ASD's prevalence that will not vary significantly from region to region or year to year. The solutions emerging thus far from this debate have involved conducting more research.

I believe that these and other findings indicate, however, that these prevalence estimates are strong enough to support a second goal for prevalence research: to generate hypotheses about state and national trends in identification among community-based professionals. Do we appear to be missing a lot of children with ASD ? Are estimates reasonably similar from state to state? If not, how big is the gap between these estimates of prevalence, and the number of children actually identified with ASD by health and education specialists? If the gap is small, then it may make sense to invest in more powerful research designs in pursuit of the primary goal established by epidemiologists. But if the gap is not small, then it may make more sense to develop hypotheses regarding the reasons for these gaps, and test strategies to close them. I consider this question in the next piece in this series.