Expansion vs. Innovation?

![]() Innovation & transformation involves much more than expansion & improvement

Innovation & transformation involves much more than expansion & improvement

What research guides growth?

Not all research translates into implementation & impact when helping programs to grow.

Not all research translates into implementation & impact when helping programs to grow.

Where are the leaders?

Know what you need in a leader, and match them care-fully to your program's goals.

Know what you need in a leader, and match them care-fully to your program's goals.

Are you ready to grow?

Can you incorporate the new approaches, stark feedback, and partnerships needed?

Can you incorporate the new approaches, stark feedback, and partnerships needed?

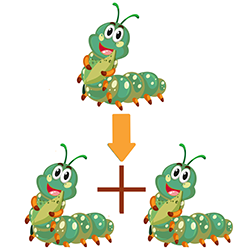

Countdown to startup

![]() A timeline for the leadership, resources, and preparation needed to launch

A timeline for the leadership, resources, and preparation needed to launch

Coming Soon

Failure to Launch: Starting new programs of ASD services and training

Do You Need a New Leader?

July 28, 2017

Eager to learn more about a program eager to launch? Begin by looking for a posting. Of course, every program will be convinced that they are the most innovative and progressive in the region or country, offer unparalleled benefits, and great quality of life. In this section, I outline how the decision to post for a leader, and how the posting process itself, can predict whether a launch will fizzle. This includes

Eager to learn more about a program eager to launch? Begin by looking for a posting. Of course, every program will be convinced that they are the most innovative and progressive in the region or country, offer unparalleled benefits, and great quality of life. In this section, I outline how the decision to post for a leader, and how the posting process itself, can predict whether a launch will fizzle. This includes

Warning Signs in leadership that could suspend or abort a launch, and

Warning Signs in leadership that could suspend or abort a launch, and

All Clear Signs in leadership that could help to re-start a launch

All Clear Signs in leadership that could help to re-start a launch

In subsequent pages, I list the specific qualities those seeking to recruit a new leader should consider when evaluating candidates, depending on whether they are striving for expansion and improvement, or innovation and transformation. In most cases, this includes solutions when candidates appear to fall short of the qualities desired.

Deciding whether you need a new leader

One of the very first decisions will be whether a new leader is needed. This decision, and the process by which it is reached, tells you a lot about the organization and its potential for a successful launch. The lesson most organizations learn too late is that improving and expanding programs of services in a coordinated and sustainable way requires a lot of planning, expertise, and leadership. This mistake will affect every stage of the process, not just recruiting a new leader, but preparing the parent organization for the expected changes, and outlining a timeline. The examples offered elsewhere in this section illustrate why these kinds of mistakes are especially likely for more ambitious proposals. Here are some specific pitfalls and opportunities, even at this early stage.

Just adding one or two new staff rarely achieves the kind of significant expansion or improvement a grantor seeks

Just adding one or two new staff rarely achieves the kind of significant expansion or improvement a grantor seeks

An organization decides to make expansion and improvement of ASD-related services and training. What do they do? They just hire one or two new staff, and perhaps drawing attention to this new priority by assigning them a title of ASD director, but without according them any real authority, assigning them any real resources, or undertaking any other organizational changes.

In countless hospitals, school districts, state governments, (Doehring and Rozell, 2014), and private organizations across the country, this kind of effort is rarely sufficient to achieve a significant expansion, and never leads to transformation. Sometimes the specialist is designated with a title suggesting some authority (ASD Director). Other times, they are fresh out of school. In either case, when this person is somehow expected to initiate change despite the lack of experience, resources, or real authority, chances are that the agency is only concerned with giving the appearance of progress so that they might woo prospective donors, or appease disgruntled advocates.

Of course, adding one or two staff may help to increase ASD-related services or training, but only in specific circumstances. In these cases, the extent of the impact is tied directly to the background of the staff, and any additional authority or resources assigned. What are the best-case scenarios? Adding 1-2 staff will increase capacity for already existing services and training, or may help launch a new specific program of services or training already in use elsewhere if the staff has the required background to lead it. Add some resources or some real authority to committed staff members in an organization open to change, and gradual but fragile improvement may occur over a period of years.

A tug of war over new leadership tests the grantee's commitment to build capacity and not just a resume

A tug of war over new leadership tests the grantee's commitment to build capacity and not just a resume

A launch can also be crippled when a grantee decides he or she could probably just lead this program too. Sometimes this is a very natural fit: after all, the grantee has already outlined the program's parameters. But the grantors funding a program start-up are justified in asking a critical question: does the grantee want to build capacity, or just their own career? The answer is very important, but not often clear.

Without ambition, many grantees would probably never bother writing grant applications, but this same ambition can cause a new program to fizzle on the launchpad. How?? As described elsewhere on this site, program development often requires a significant commitment of time and resources, even for the those experienced in launching new programs. Unless the grantee can off-load other responsibilities, it is unlikely they can free up the time needed for a new program launch, especially for more ambitious programs. In the euphoria surrounding the successful funding of a start-up, it is easy to see how an ambitious grantee might begin to believe they can simply take on more responsibility, especially if it opens doors to even greater funding opportunities in the future. And for the grantee who has never undertaken such a project before, it becomes even easier to under-estimate the effort likely to be required. A grantee who is threatened by the competition a new program leader might bring to the department may also err towards trying to take on these new responsibilities themselves.

The result? The grantee is simply overloaded, and they either cannot get a program off the ground, or can do so only by cutting corners. And grantees vulnerable to this ambition will be even more reluctant to admit their mistakes and adjust course. It can be difficult for grantors to disentangle valid reasons for a failing launch from the excuses offered by a grantee desperate to dissemble.

For grantees ultimately seeking to create new capacity, the calculus is very simple: they recognize that they will simply never increase capacity without new blood and new partnerships. As the program becomes more innovative and the expansions more ambitious, the challenge of recruiting existing leaders or nurturing new ones becomes pivotal to a successful launch. A grantee experienced in program development or committed to building capacity will be able to clearly articulate this plan, elements of which are described elsewhere.

Shifting an existing leader into a new role while adding new resources to fill gaps can increase capacity

Shifting an existing leader into a new role while adding new resources to fill gaps can increase capacity

As described above, sometimes the grantee is already a leader in the organization, and they are writing a proposal for the program they hope to lead. This is an excellent strategy to expand the organization's capacity, as long as it includes a plan to backfill the grantee's responsibilities with a new hire. Why?

First, this plan eliminates the often frustrating search for a new leader. This affords the successful grantee the opportunity to pass their institutional knowledge to their successor, and perhaps directly facilitate a new partnership when the grantee's old and new programs must work closely together.

Second, this demonstrates the organization's capacity to re-invest in successful staff, and motivates others. Perhaps the grantee's successor is an opportunity to reward a committed staff member with a promotion, and sends a message to others in the organization with similar ambitions. This builds on another important lesson: the need for a long-term strategy to grow expertise within your organization, because of the scarcity of expertise elsewhere. But otherwise a very different message is sent: the rewards of ambition is more responsibility without recognition or resources... a great way to send the best staff to your competitors!

There are some risks. Growing a leader from within means that they inherit whatever dysfunctional processes have might already infected an organization's culture. Rewarding an ambitious grantee or promoting a staff member to backfill the grantee's responsibilities can also send the wrong message if the grantee is not carefully vetted. And the grantee's promotion can be disruptive for others jealous of the new recognition and responsibilities.

Posting for a new leader

When an organization decides to look for a new leader, the posting offers a window into the planning (or lack thereof), and ultimately the prospects, for the program. And look at the warning signs listed below. Some of these might help donors, advocates, or other stakeholders to urge some last minute adjustments to the grantee to salvage a program launch.

A promptly filled posting portends a successful launch

A promptly filled posting portends a successful launch

In the case of a properly planned launch with a reasonably constructed leadership position in a well-functioning organization using sound recruitment strategies, a leader can be found within 10-12 weeks of the initial announcement of the intent to launch. It is not just the sign of good planning, it can help the program to meet its early goals.

The unrealistic posting signals poor planning and organization

The unrealistic posting signals poor planning and organization

The posting for a leadership position captures the qualifications and experience the grantee expects the person to bring. But sometimes the posting is patently unrealistic; for example, a posting for an experienced practitioner with a track record of research funding AND publications AND demonstrated skills in program development and leadership, to launch a program in a setting undistinguished in terms of research, clinical services, or fundraising. Elsewhere in this site, I describe how the traditional career path for the aspiring clinician-researcher is in fact a minefield for those seeking meaningful experience in community-based settings, and which makes this kind of posting questionable.

Other leadership postings can almost be bizarre. A recent example was a posting to help create an innovative program of services, seeking a master's level professional with experience developing programs of services for people with ASD. Aside from the fact that the posting did not require any training or experience in delivering services (more on that below), I could not think what career path might offer that kind of experience to someone with a master's degree. This kind of posting might be appropriate for a grantee simply seeking to replicate a well-established program that offers plenty of specialized support during start-up (like a Project SEARCH site), but not a program expected to be truly innovative. The programs most likely to take off and replicate are designed around the staff and leadership likely to be available, not the other way around.

The delayed or never-ending posting signals a lack of flexibility and creates cascading problems during the critical early phases

The delayed or never-ending posting signals a lack of flexibility and creates cascading problems during the critical early phases

A delay in the posting itself, especially relative to the announcement of the initiative, is a bad omen. As described later in this series, the desired qualifications of a leader should be established early in the process, as soon as the outlines of the anticipated program begin to take shape. A delayed posting is a sign that the grantee has not done their homework or simply cannot reach a decision about the leader they seek. These delays might also signal the parent organization's lack of commitment to move the process forward, or a cumbersome hiring process, which could delay bringing other key staff in quickly.

A posting that remains unfilled for 4 to 6 months or longer signals all of the above problems, and portends others. For example, the failure to recruit viable candidates despite reasonable efforts should provide grantees with information about the likely candidate pool, and should provide the grantor with information about the parent organization's ability to adjust on the fly. Will the grantee learn the important lesson that there is no natural pipeline of new leaders? Can the grantee effectively adjust the launch or reconfigure the program goals or identify some of the other resources listed below, and then re-post a modified position? And the failure to recruit viable candidates should prompt a grantee to begin to panic. If none of this occurs, a grantor should begin to wonder whether the program's proponents have the commitment and the flexibility needed.

The cumulative, downstream impact of each of these delays should not be under-estimated. If combined with any other delays (like in creating strategic partnerships or hiring core staff), these could doom a successful program launch. The impact is deceiving, because it occurs in slow motion, and sometimes is only evident 6 to 12 months later. But the complexity of launching a new program also means that there may be few opportunities to catch up. Those experienced in program development will will recognize these signs and take prompt action.

Related Content

On this site

Who can lead an expansion?

Who can lead an expansion?

Who can lead transformation?

Who can lead transformation?

Warning Signs that could suspend or abort a launch

Warning Signs that could suspend or abort a launch

All Clear Signs that could re-start a launch

All Clear Signs that could re-start a launch

Expansion vs. Innovation?

![]() Innovation & transformation involves much more than expansion & improvement

Innovation & transformation involves much more than expansion & improvement

What research guides growth?

Not all research translates into implementation & impact when helping programs to grow.

Not all research translates into implementation & impact when helping programs to grow.

Where are the leaders?

Know what you need in a leader, and match them care-fully to your program's goals.

Know what you need in a leader, and match them care-fully to your program's goals.

Are you ready to grow?

Can you incorporate the new approaches, stark feedback, and partnerships needed?

Can you incorporate the new approaches, stark feedback, and partnerships needed?

Countdown to startup

![]() A timeline for the leadership, resources, and preparation needed to launch

A timeline for the leadership, resources, and preparation needed to launch

Coming Soon

X

My Presentations and Publications

(2014) With Denise Rozell. Beyond the Drawing Board: How statewide planning can generate and sustain improvement. Invited Workshop, National Autism Leadership Summit, Columbus, OH

(2014) With Denise Rozell. Beyond the Drawing Board: How statewide planning can generate and sustain improvement. Invited Workshop, National Autism Leadership Summit, Columbus, OH

Guideposts

![]() Other Lessons There is no natural pipeline of leaders trained and experienced in undertaking comprehensive program development

Other Lessons There is no natural pipeline of leaders trained and experienced in undertaking comprehensive program development

![]() Other Lessons Improving and expanding services in a coordinated and sustainable way requires planning, expertise, and leadership

Other Lessons Improving and expanding services in a coordinated and sustainable way requires planning, expertise, and leadership

![]() Other Lessons To expand competence or to increase capacity, you must cultivate new experts recruited within the organization

Other Lessons To expand competence or to increase capacity, you must cultivate new experts recruited within the organization