A Model Research Roadmap

A diagram illustrates how each stage of screening research helps maintain progress towards improved diagnosis.

An Integrated Network

Relationships between services, training, policy, and advocacy reveals a unique role for research

Stages of Research

Each stage of research has a difference influence on the integrated network and on better outcomes

The CHAT+ Pilot Study

Applying the roadmap to 25 years of research invoving all versions of the CHecklist for Autism in Toddlers

Milestones

What distinguishes implementation and clinical research? Different participants, measures, and designs.

Resources Required

Each stage of research requires different training, funding models, partnerships, and scholarship.

Other Components

A structure that breaks progress down into manageable steps can help close persistent gaps identified via research.

Coming very soon

An Applied Research Roadmap for ASD Screening: Stages of Research

Clinical Research

June 20, 2019

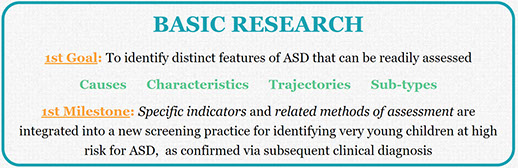

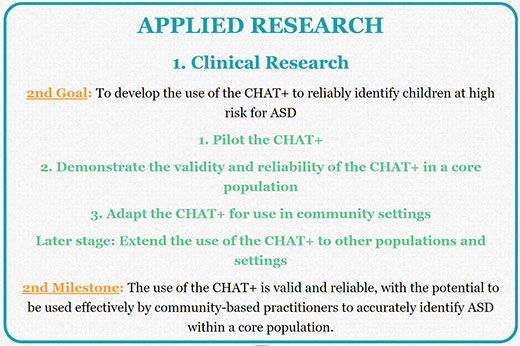

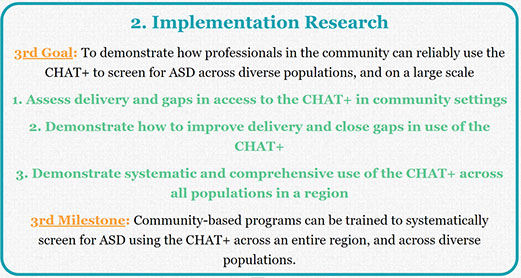

Leaving Basic Research As the first stage of Applied Research, clinical research provides the initial demonstrations of the validity, effectiveness, and applicability of a new practice intended to achieve an important outcome in a clinical population of people with ASD. It is distinct from subsequent stages of Applied Research described elsewhere, like implementation research (e.g., evaluating the use of the practice in community settings and on a large scale), and other forms of applied research (e.g., that explore the relation to other outcomes and other practices). We have reached the milestone marking the transition from clinical to implementation research when we have confirmed that the practice is valid and reliable, with the potential to be used effectively by community-based practitioners within a core population.

As the first stage of Applied Research, clinical research provides the initial demonstrations of the validity, effectiveness, and applicability of a new practice intended to achieve an important outcome in a clinical population of people with ASD. It is distinct from subsequent stages of Applied Research described elsewhere, like implementation research (e.g., evaluating the use of the practice in community settings and on a large scale), and other forms of applied research (e.g., that explore the relation to other outcomes and other practices). We have reached the milestone marking the transition from clinical to implementation research when we have confirmed that the practice is valid and reliable, with the potential to be used effectively by community-based practitioners within a core population.

On our Roadmap to achieving population impact, Applied Research begins once we have built a prototype of car (a practice to pilot) that we are ready to test drive on a closed track. Is it reliable? Does it handle well enough? And so we take it on short trips to some familiar destinations under controlled conditions. Once it proves to be reasonably reliable and useful, we feel comfortable taking it to the next level: testing it on all kinds of real trips with all kinds of real people, and scaling it up for a real world market via Implementation Research.

We first began to use these specific definitions of Clinical Research in our systematic review seeking to categorize the primary objective of every research study focused on the CHAT+. These definitions may continue to evolve as this review is completed, and begins to include secondary objectives. More information about the specific milestones (e.g., from Basic to Clinical Research, and from Clinical to Implementation Research) and the other core components of a Research Roadmap are available elsewhere. A bibliography of all CHAT studies referenced below is available for download. An overview of the relation of research to other elements of the integrated network is available elsewhere on this site, while a more complete review if included in my 2013 book.

What is applied research?

Many different kinds of research studies are identified by their authors as possibly relevant to assessment and treatment. But which ones can we really consider to be applied? We defined applied research as any study that directly demonstrates the use of a clinical practice used by professionals providing services to to achieve an important clinical outcome for an identified population of people with ASD.

While more specific definitions are linked to each term underlined in blue above, some specific notes might be useful here. First, we focus on those studies whose findings provide specific and immediate guidance to those interested in assessment and intervention. While there are many studies with possibly exciting implications for future research or practice, parents or professionals responsible for making a specific decision about assessment or intervention need to know what concrete guidance this research study might offer right now, not what future work might conclude. The reliance on clinical practices assures immediate and specific guidance.

Second, we focused on research that sought a clinical outcome. For other practices, this might eliminate research demonstrating the benefit of assessment or the effects in interventions for a group of individuals with characteristics but not a formal diagnosis of ASD. Assessing research on the CHAT+ is different because, by definition, screening involves children not (yet) diagnosed with ASD. In this case, we elected to focus on research studies in which the instrument contributed to the determination of a diagnosis of ASD. This effectively eliminated research that some might consider applied, like studies that only used the CHAT+ to cross-validate another related instrument (Gardner et al., 2013; Glascoe, Macias, Wegner, & Robertshaw, 2007), or that only utilized the CHAT+ to assess ASD risk status (Altay et al.,2017; Ts et al., 2018), without ever specifically determining a diagnosis.

As discussed elsewhere, the transition into clinical research creates new demands on researchers. This includes demands on their training and experience, as well as greater flexibility with respect to the kinds of research and scholarship required. Attaining the milestone marking the transition from clinical to implementation research also creates a wide range of exciting new opportunities for researchers to engage with other elements of the integrated network.

Phases of Clinical Research

Basic Research Clinical Research1. Pilot practice2. Demonstrate its validity and reliability3. Adapt it for use in community settingsLater, extend it to other populations & settings

Clinical Research1. Pilot practice2. Demonstrate its validity and reliability3. Adapt it for use in community settingsLater, extend it to other populations & settings Training

Training Implementation ResearchPhase 1: Pilot Practice

Implementation ResearchPhase 1: Pilot Practice

In Clinical Research, we begin by piloting a specific practice with individuals identified with ASD (or, in the case of a screening tool, considered at risk for ASD). This includes studies that sought preliminary validation of a new clinical tool or technique prior to widespread implementation. For practices centered on assessment, this would also include any studies that tested changes to the items, format, or scoring of a tool. This first phase of clinical research typically occurs on a relatively smaller scale with respect to the number of participants, professionals, and settings involved.

Each version of the CHAT+ involved at least one study that sought preliminary validation, first of the CHAT (Baron-Cohen, Allen, & Gillberg, 1992), and later the M-CHAT (Robins, Fein, Barton, & Green, 2001) and Q-CHAT (Allison et al., 2008). This also included any other significant modifications to the tool itself up to a new version, like new items, new scoring criteria, new mechanisms of administration that were included in the M-CHAT R/F (Robins et al., 2014).

Phase 2: Demonstrate the validity and reliability of the practice for at least a core population

The next phase - demonstrating the practice's validity and reliability - is familiar to most developers of assessment instruments. This involves testing a new practice more rigorously and on a larger scale through other research. At some point this work is replicated beyond the original research team, providing additional confidence in the findings. For assessment tools, this can include a broad range of tests of the tool's reliability and internal / external validity. Other tests are more specific to the type of instrument being considered. For example, screening tools like the CHAT+ also require tests of sensitivity (the likelihood that the test detects all relevant members of the population of interest) and specificity (the likelihood that everyone detected by the test has the condition of interest).

Each version of the CHAT included at least one subsequent study designed to provide additional information about the instrument's validity and reliability. For example, Baron-Cohen followed his 1992 pilot research with an ambitious validation study involving a very large community sample (Baron-Cohen et al., 1996). Eaves and her colleagues considered the sensitivity and specificity of the M-CHAT relative to the Social Communication Questionnaire in a sample of 2- and 3-year olds (Eaves, Wingert, & Ho, 2006). Hardy and her colleagues sought to compare the performance of the M-CHAT R/F with the Ages Questionnaire (Hardy, Haisley, Manning, & Fein, 2015). In our systematic review of the M-CHAT, almost one-third of all studies were categorized in this phase.

This importance of this phase in evident in the history and evolution of the CHAT. The first large-scale validation study of the CHAT revealed a fundamental psychometric limitation; its low sensitivity meant that it was likely to miss more children than it identified (Baron-Cohen et al., 1996). The M-CHAT sought to address this issue by converting items into a questionnaire completed by a parent, and then establishing risk based on relying on a summed score of indicators rather failure on a specific pattern of key items (Robins, Fein, Barton, & Green, 2001) . This change also greatly simplified its use, by eliminating the need for observations by a clinician. Subsequent revisions to the M-CHAT capitalized on a feature of the original CHAT - the use of a second administration to confirm risk status that seem likely to have improved its sensitivity and specificity (Robins et al, 2014).

A first goal: Establish core indicators of validity within a core population

With respect to assessment tools, a lot has been written about the importance of this phase, the many different tests of validity and reliability, and the thresholds that should be adopted for each test under different circumstances. It is not clear, however, if there is a universally-recognized standard to guide a decision to implement a practice more broadly. How much information about the reliability and validity of a practice must be gathered it can be used outside of a research setting? Before it can be confidently integrated into the daily practice of a community-based program. Informal observations conducted during our systematic review of CHAT+ research suggests that researchers considered a wide range of tests of validity and reliability. The next phase of our review will involve systematically categorizing these studies by the types of tests utilized.

The opportunity to establish some standard is complicated by the fact that the validity and reliability of the CHAT+ appear to vary significantly as a function of the subpopulation studied. It works more or less effectively depending on the age of the child, and the presence of co-occurring conditions and other risk factors (i.e., having a sibling already identified with ASD. We therefore plan on also breaking tests of reliability/validity down by subpopulation.

Undertaking the full-range of tests of validity/reliability on the full range of populations therefore takes time. How many such tests must be completed before a emerging practice is ready to be tested outside of highly-specialized settings, or integrated more broadly into community-based programs? We think we can break this decision down into several phases.

- Define a core population for which the validity of the test appears more assured, based on the age and presence of other characteristics. Ideally, this core population is one commonly seen and readily identified by community-based practitioners. For example, a core population of children between 16 and 30 months of age and who may or may not present with co-occurring developmental delay is more prevalent than a population of children 24 to 30 months of age without previously identified developmental delays. When the target population is commonly seen and readily identified by community-based practitioners, it is easier to justify the investments in subsequent phases of clinical research (i.e., to adapt the practice to community settings), and the later investments to develop the necessary training materials and undertake implementation research. This is why we did not include research adapting a practice to another culture or language, or research exploring the utility of a practice in those whose ASD is accompanied by other conditions, as necessary to begin implementation research. While such research will become necessary in later phases of implementation research (i.e., seeking to demonstrate utilization on a regional level), it is not necessary to begin to develop associated training materials, or to begin to assess gaps in implementation.

- Consider different phases of reliability/validity testing that balance the need to meet a rigorous standard while exploiting the potential for immediate benefit. We would argue that some tests are likely essential to establishing a practice's reliability and validity before implementation outside of specialized research settings is to be considered. In the case of a screening instrument, for example, this could include tests of sensitivity and specificity. Other tests may be more important to refining recommendations regarding the utilization of a practice - e.g., to better characterize false negatives, or those children originally missed by the CHAT+ but identified with ASD at a later age. For this reason, we will include some of these focused validation studies in a later phase of clinical research. Still other forms of validity might warrant more intensive examination once the immediate benefits of a practice have been established. These include the evaluation of more distal impact of research, included as a phase of Other Applied Research. In the case of the CHAT+, this includes research underway to establish whether early ASD screening through instruments like the CHAT+ actually leads to early and effective intervention, a long-held assumption recently challenged in controversial guidelines issued by the Preventative Services Task Force.

Phase 3: Adapt the practice for use in a community setting

Our final phase of Clinical Research seeks to demonstrate that community-based professionals outside of the original research team are able to utilize the practice effectively. It may consider the need to offer more concrete guidance regarding the use of the practice, especially relative to other overlapping practices. This research may reveal the potential benefit of minor adaptations to facilitate administration. Such research provides another measure of the practice's validity. It can help to justify the investment needed to develop the training materials essential to broader implementation, like the clinical guidance and training manual we developed for the CHAT. The CHAT+ is somewhat different from other practices to which our Roadmap might be applied, because it is designed from the outside to be administered by community-based professionals.

This kind of research took several forms in the case of the CHAT+. For example, Baron-Cohen's large-scale study of the sensitivity of the CHAT also served to demonstrate that the CHAT+ can be used effectively by community-based practitioners under real-world settings and conditions (Baron-Cohen et al., 1996). Wiggins and her colleagues explored how to integrate use of the M-CHAT with broadband screeners. Still other researchers tested digitally-administered versions of the M-CHAT (Campbell et al., 2017), in some cases accompanied by decision-making support (Sturner et al., 2016).

Later phases: Extend the practice to other populations and settings.

A central goal of our Roadmap is to identify when there is sufficient evidence to support a shift to the next phase of research. In part, this reflects our recognition that ASD is complex: it is a spectrum disorder that can include a wide range of co-occurring conditions that influence assessment, treatment, and outcomes. This also reflects our recognition that our world is complex, with people from many different backgrounds and circumstances that may sometimes necessitate adaptations to the practice. And many practices can be administered across a range of settings by a range of professionals. While the range of professionals and settings potentially involved in the administration of the CHAT+ is limited, we can readily imagine that this variability might be important for other practices.

These other types of clinical research are needed to address the complexity of ASD, our world, and the professionals and settings providing support. While the final phase of implementation research will eventually require data to support the use of a practice across the full range of populations and settings, we nonetheless contend that the initial phases of implementation research can begin as long as all earlier phases of clinical research have been completed, for at least a core population.

Adapt the practice for other cultures

Especially in the case of paper and pencil measures, it is important to validate translations and adaptations of an instrument for other languages and cultures. For example, Koyama and colleagues explored the validity of a Japanese translation of the CHAT (Koyama et al., 2010). More than a dozen studies sought to translate and adapt the original M-CHAT or M-CHAT R/F for a wide range of languages and cultures, including French (Baduel et al., 2017), Spanish (Canal-Bedia et al., 2011), Chinese (Guo et al., 2018), and Arabic (Eldin et al., 2008).

Explore the validity of the practice with sub-populations

Other clinical research might seek more detailed information on the validity of the practice for a specific sub-population of eligible, beyond the core population referenced above. With regards to the CHAT+, some of these studies explored validity and usefulness with subpopulations defined by age applicability to: outside of the originally recommended 18- to 30 month age range, :

Some of these sub-populations were defined by the presences of co-occurring conditions that might have raised the risk for ASD. For example, Scambler and his colleagues explored the validity of the CHAT in screening for ASD in a population of toddlers with Fragile X (Scambler, Hepburn, Hagerman, & Rogers, 2007). Much more extensive work with specific high-risk populations has been done with the M-CHAT. This includes exploring its validity and usefulness with siblings of children already identified with ASD (Kumar, Juneja, & Mishra, 2016), children born preterm (Dudova et al., 2014), children with very low birthweight (Beranova et al., 2017), and children with neurofibromatosis (Tinker et al., 2014) or Down syndrome (DiGuiseppi et al., 2010).

Extend analyses of validity

Still other clinical research might explore other questions about the validity of a practice that might become important as a practice is scaled up to be delivered systematically across a region, but that need not be answered to begin implementation research. In the case of the CHAT+, this included additional analyses to better characterize false negatives, or children determined not to be at risk based on an initial administration of the CHAT+ but who are nonetheless diagnosed with ASD at a later age (Beacham et al., 2018; Matson, Kozlowski, Fitzgerald, & Sipes, 2013).For our review currently in development, we collapsed these additional studies of validity into the earlier phase of clinical research on validity and reliability.

Related Content

Other Stages of Research

Basic Research

Basic Research

Coming soon!

![]() Implementation Research

Implementation Research

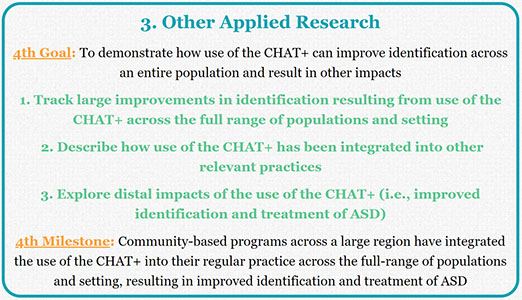

Other Applied Research

Other Applied Research

Coming soon!

Other content on this site

A Research Roadmap based on the CHAT+

Hover over phases for details

APPLIED RESEARCH

BASIC RESEARCH

1. Clinical Research

2. Implementation Research

3. Other Applied Research

A Model Research Roadmap

A diagram illustrates how each stage of screening research helps maintain progress towards improved diagnosis.

An Integrated Network

Relationships between services, training, policy, and advocacy reveals a unique role for research

Stages of Research

Each stage of research has a difference influence on the integrated network and on better outcomes

The CHAT+ Pilot Study

Applying the roadmap to 25 years of research invoving all versions of the CHecklist for Autism in Toddlers

Milestones

What distinguishes implementation and clinical research? Different participants, measures, and designs.

Resources Required

Each stage of research requires different training, funding models, partnerships, and scholarship.

Other Components

A structure that breaks progress down into manageable steps can help close persistent gaps identified via research.

Coming very soon

X

My Related Publications

(2019). A systematic review of research involving ASD screening tools: A roadmap for modeling progress from basic research to population impact. International Society for Autism Research, Montreal, CA. May View handout.

(2019). A systematic review of research involving ASD screening tools: A roadmap for modeling progress from basic research to population impact. International Society for Autism Research, Montreal, CA. May View handout.

(2019). Clinical research to develop tools to improve ASD Identification: A comprehensive review of projects funded in the US from 2008 to 2015. International Society for Autism Research, Montreal, CA. May. View handout

(2019). Clinical research to develop tools to improve ASD Identification: A comprehensive review of projects funded in the US from 2008 to 2015. International Society for Autism Research, Montreal, CA. May. View handout

(2018). Priorities Established by the Combating Autism Act for Improving ASD Identification: Looking Beyond Ideas and Instruments Towards Implementation. View handout. International Society for Autism Research, Rotterdam, NL. May. View handout.

(2018). Priorities Established by the Combating Autism Act for Improving ASD Identification: Looking Beyond Ideas and Instruments Towards Implementation. View handout. International Society for Autism Research, Rotterdam, NL. May. View handout.